Responding to the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe, massive mobility restrictions were imposed in the Schengen area. While the internal Schengen border controls have mostly been lifted, the uncoordinated national reopening of its external borders have led to a patchwork of border regulations. An original analysis of the unilateral steps taken by Schengen states to reopen borders to third countries is presented here. In order to avoid any serious damage to the functioning of the EU borderless area, members need to stick to common rules and act in together, rather than in a single-handed fashion.

The Covid-19 pandemic has not only radically impacted the way in which humans on the European continent socially interact with each other, but it has also suspended the freedom of movement that Europeans have grown accustomed to across their own continent.

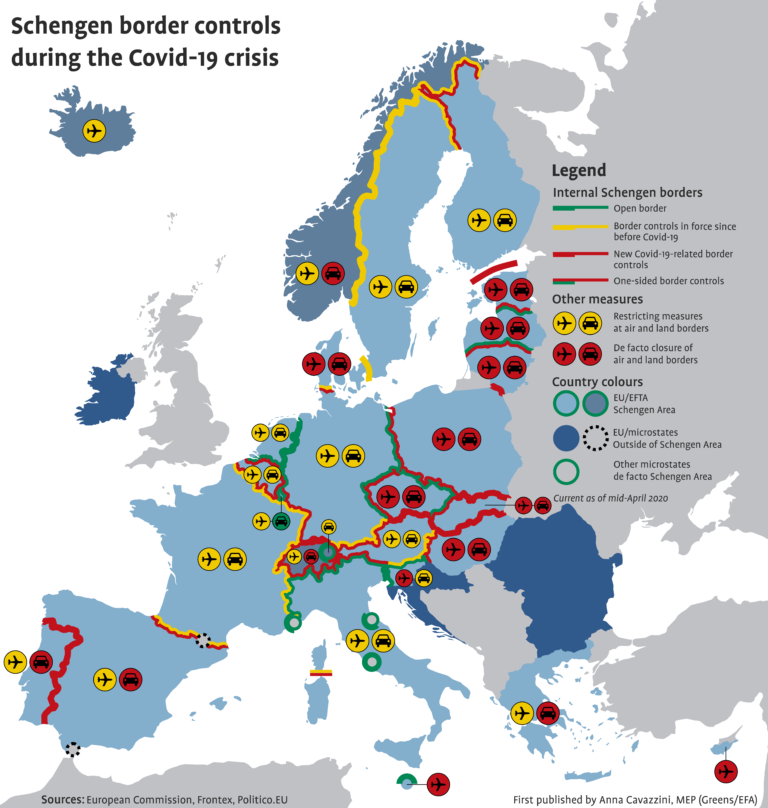

By mid-April 2020 most member states of the Schengen area, which usually allows border-free travel within its own territory, had unilaterally closed the borders to their neighbours. This led to a patchwork of travel restrictions (see map first developed in cooperation with Anna Cavazzini, MEP). At first, it mainly impacted the free flow of goods vital for the European economy, including medical equipment, but ultimately it hit individuals the hardest. In effect, Europeans were ‘locked’ into their countries of residence, effectively separating families and couples from each other.

Since then, important efforts have been made by European governments to reopen Europe’s internal Schengen borders. This was largely successful, as, by the middle of June, most internal borders checks had been abandoned, families reunited, and Europeans even started to go on summer holidays abroad.

This rapid and coordinated lifting of internal travel restrictions would have been predicted by few observers at the height of the pandemic and is testament to the importance of free travel across our continent. However, while a return to normality can be seen as a big achievement, it is now at an even greater risk at its external borders. Similarly to Schengen’s peril during the refugee crisis, this is due to significant disagreements amongst its member states, and can only be overcome through greater cooperation.

Schengen’s external border problem

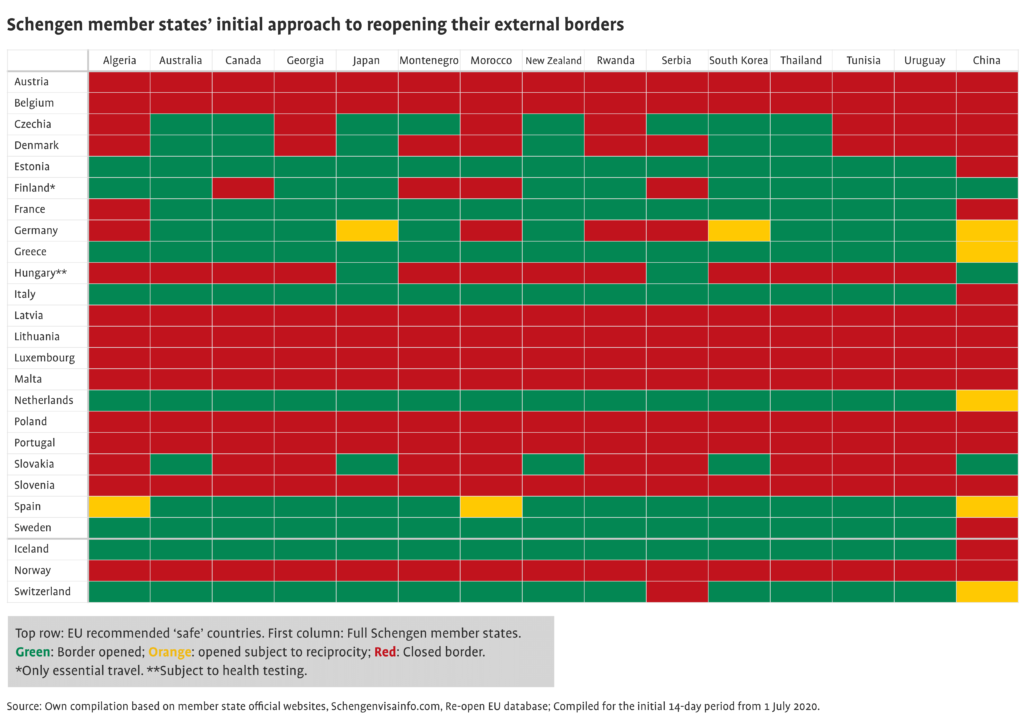

All members of the Schengen area had agreed in mid-March to close Europe’s external borders at the height of the pandemic. Much like this initial closure and how the reopening of Schengen’s internal borders was a coordinated move amongst the EU’s institutions and the governments of its member states, a similar approach was to be applied to the external borders as of 1. July. The idea was to gradually reopen to the rest of the world, based on scientific criteria that would keep the risk of infections as low as possible and deflect criticism that the EU’s decision was politically motivated. Consequently, it was decided that member states could reopen their borders to residents of 14 third countries (plus China if it allowed Europeans back in), subject to revision every two weeks, as well as to travellers with a special purpose such as university students or family members.

However, as the ultimate decision to do so remains with the authorities of each individual member state, this list only constituted a recommendation, with member states urged to follow the guidelines developed. It is at this stage of the reopening process that all sense of pan-European coordination disappeared. As the table shows (see below), many EU member states indeed reopened their borders as recommended in the initial 14-day-period. Others, however, only followed parts of the recommendation or did not reopen their borders at all. There were also disagreements as to special purpose travellers, as only some EU member states’ considered a third country member of an unmarried couple worthy of entering their territory. For instance, Germany has opened its border to 11 countries, Czechia to 8 and Belgium to none. Some EU member states like Croatia even ignored the list altogether and let everyone enter their territory.

This development puts the hard-fought-for reopening of Schengen’s internal borders at peril. If countries like Belgium, which has kept its borders technically closed to the residents of all third countries, are serious about this policy, they would have to close their internal Schengen borders again. If not, a citizen of, say, Georgia, would be able to fly to the Netherlands which has reopened as per the EU’s recommendations, and then travel across the internal Schengen border to Belgium. If Belgium wanted to make sure that its rules are applied, it would have to close its border to the Netherlands again. The resulting uncertainty about which citizens can travel where is not only criticized by airlines and airports, but also by many binational couples and families. Using hashtags like #LoveIsNotTourism, they are urging governments for their right to be reunited.

As this example illustrates, the lack of actual coordination on the Schengen area’s external borders has once more created a patchwork of travel restrictions incompatible with managing the next phase of the pandemic at the European level and as necessitated by the continent’s open borders. To make matters worse, some member states have opted to ignore the coordinated approach altogether. For instance, Hungary has allowed citizens of countries such as the United States or Russia to enter. Similarly, Malta has allowed residents of countries not included on the EU’s list to travel there. This uncoordinated behaviour ultimately risks politicising other countries’ reopening to the EU, who may in turn decide in a game of tit-for-tat to reopen their borders for some Schengen countries only.

Our Blog

Corona & Society: Reflecting on the crisis

What can society and politics learn programmatically and conceptually from the crisis?

Making Schengen last: Better governance to the rescue

The Covid-19 pandemic has once more put serious design flaws in the governance of the Schengen area to the fore. It is simply impossible to maintain the EU’s open internal borders without a joint management of those to the outside world. While the refugee crisis has proven for this to be the case at the EU’s external land and sea borders, the current pandemic shows that this also applies in the glass domes of the EU’s international airports.

The current situation ultimately demonstrates that abolishing common internal borders does not function without a common management of the EU’s external borders. In the long-term, the functioning of the Schengen area needs to be altered for it to survive. This requires a common application of common rules that are more than mere recommendations. In line with all other areas of European integration, only the European Commission is suited to make such choices without succumbing to national interests.

Until then, it is the responsibility of all member states, and particularly of the EU’s rotating Council Presidency currently held by Germany to urge the others to cooperate. An initial sensible step to show the EU’s unity is for all Schengen area states to let separated couples’ reunite, as demanded by the #LoveIsNotTourism campaign.

Schengen member states’ approach to reopening their external borders

A German version of this article was published in cooperation with our media partner Euractiv on their website.