European politics has become dominated both by new populist actors and the refugee crisis. If the left is to live up to these two challenges in the coming months and years, it needs to re-establish its capacity to set the political agenda away from questions of immigration and security

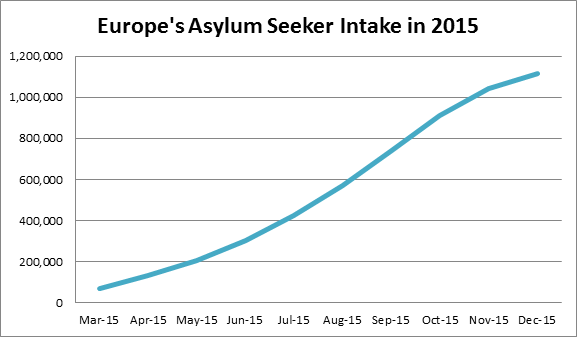

According to data published by Eurostat, close to 1 million asylum seekers arrived in the European Union in 2015. Presumably several hundred thousand additional migrants also arrived, who took advantage of the lack of border controls and the unpreparedness of governments, and were thus not registered in any EU database. In western Europe, the crisis exacerbated domestic political debates on immigration and integration, but it had an even greater effect on those central and eastern European nations where immigrants form less than four or five per cent of the total population. In these countries, voters are faced for the very first time with one major effect of globalisation: the possibility or necessity of cohabiting with people who have a different culture or religion than the majority of the population. The concept of second- or third-generation immigrants is also virtually unknown in these countries. Therefore, the advantages and disadvantages of multiculturalism, and the arguments for and against it, are completely unknown to voters in these states, with the exception of a narrow elite.

While voters of leftwing and centre-right parties in western Europe saw in migrants helpless, persecuted populations who were escaping from war, people in central and eastern Europe (but also in a number of western countries) saw the same populations as strangers from an alien culture who were flouting national and EU borders and rules, ‘breaking into’ Europe, and putting even more pressure onto communities scraping along in an economic crisis. Although the majority of leftwing voters look at the migrant crisis primarily as a question of solidarity, a very significant proportion of Europeans see it more as an issue a security, identity and economic threat.

Of these different concerns, presumably humanitarian and solidarity-based arguments would have been the strongest among voters during the golden age of European integration, up to the 2000s. But in 2015-16, this is no longer necessarily so, and the anti-migrant, nationalistic mood is bolstered by the rise in strength, and even election to government, of populist politicians.

Populists in power

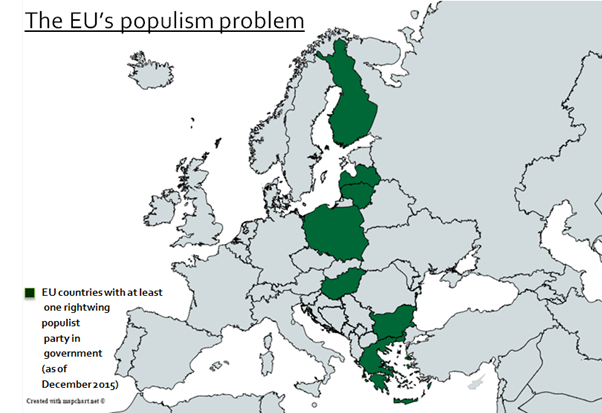

Last year, 2015, rightwing and leftwing populist parties achieved heretofore unseen power in numerous European states. Yet their rise did not begin last year, the migrant crisis only accelerated an already existing trend. We can see from the results of the 2014 elections to the European parliament that in 11 member states out of 28, at least one fifth of voters voted for populist parties.In 2015, out of the 28 EU member states, 25 had at least one populist party that received enough votes to gain seats in its national parliament.

Furthermore, in most countries the populist parties are no longer simply protest parties or challenger parties that are not preparing for actual governance. Populist parties have instead become organisations that are ready for governing, or indeed already holding government power. Out of the 28 EU member states, rightwing populist parties are holding parliamentary majorities and governing in two of them, in Hungary and Poland (Fidesz-KDNP and Law and Justice party, respectively). In an additional five countries (Bulgaria, Finland, Greece, Latvia and Lithuania), one member of the governing coalition is a rightwing populist party. And in Denmark, the government is receiving outside support from the Danish People’s party, another rightwing populist party. Therefore, out of the 28 governments within the EU, rightwing populism has some type of influence on eight of them.

The commonly-voiced argument against populist parties (that they are ready to bring up controversial subjects but are unable to govern), has thus been proven wrong. The successfulness of their political tenure is of course open to debate, but it is clearly visible that they are capable of achieving the basic tasks of governance, both alone and in coalitions, and can even preserve their popularity while in power.

The clash of populism and migration: The case of Viktor Orbán

The poster child of populists in power is Viktor Orbán, the prime minister of Hungary, who won the 2010 elections with a moderate rightwing programme, and achieved a two-thirds supermajority in parliament. Between 2010 and 2014 though, he followed an ever stronger populist course, destroyed the system of governmental checks and balances, and adopted a new constitution. Despite all this (or because of it), he gained another large-scale victory in 2014. Viktor Orbán’s governance is an example that shows that populist leaders do not necessarily ‘deflate’ when they switch to governing from being in opposition. Populism is useable for governing as well, not only for critiquing the elite. The actual policy ‘achievements’ of Orbán’s government are decidedly harmful to the country from most points of view, but we cannot in any case say that populist forces are unable to pose a short-term alternative to conservatives or social democrats.

Additionally, as a result of the xenophobic government propaganda, the government-funded anti-refugee publicity and the fence that was set up on the southern borders of Hungary, the country only accepted about a dozen refugees in 2015, and the social acceptance of pro-refugee policies is still steadily declining. Meanwhile, the popularity of Fidesz, the governing party, increased by more than 10 percentage points in a few months, and in December 2015 half of the decided voters were ready to vote for Viktor Orbán’s party. Because the Hungarian prime minister’s criterion for a successful resolution of the refugee crisis has for months been keeping the refugees out (and not helping them), in the Hungarian voters’ eyes Viktor Orbán has scored a victory.

Possible responses by the left

The migrant crisis and the successes that populists have achieved in gaining power puts European social democracy in front of new challenges, from several perspectives. On the one hand, the voters of populist rightwing parties include citizens who were previously accounted for as traditional leftwing voters. The dilemma that social democratic parties have been facing for some time now, of how to keep their middle-class cosmopolitan voters as well as their traditional working-class base (who have lost out due to globalisation). On the other hand, in several states, the traditional quasi-two-party system (where leftwing parties or coalitions of such parties competed with rightwing parties) has turned into a three-party system, where the left has to fight not only with the conservatives, but also with populists in order to win the elections. In fact, in several countries the populist party has taken over the role of the mainstream leftwing party as the main rival of the conservatives, and the left has shrunk to a small party with a popularity of five to 10 percentage points. Thirdly, populist answers to the migrant crisis can no longer be simply swept off the table – without engagement – by claiming that they are ‘extremis’, ‘unrealisable’, or ‘inhuman’. Populists’ responses have to the contrary become the official policies of some European governments, and the topics of a pan-European public discourse.

Leftwing parties can follow several strategies in this situation. The first possible strategy is to ‘stick to values’. In this case, helping and accepting refugees would be a question of human rights and solidarity that is more important than any other consideration. On this foundation, the left will fight the anti-refugee populists before the public, and will try to get the majority of the society behind its refugee-friendly politics. This strategy makes it possible for a party to present its straightforward, strong leftwing values; but it is nevertheless questionable whether helping refugees truly is leftwing voters’ most pressing concern. If, in the coming years, the left concentrates its energy on the migrant question, makes it its flagship issue, but neglects other concerns that touch upon its voters’ everyday lives, such as rising inequality, deteriorating social security, education or health, then its traditional voting base may erode further.

Another possibility is the strategy of ‘rational solidarity’. In essence, this would mean that the left emphasises the importance of accepting refugees, but nevertheless makes gestures to voters who demand greater security, the protection of national identity and the labour market. Although leftwing parties in several countries are visibly following this strategy, it is questionable whether a leftwing party can successfully sing from the populists’ songbook, when there are other political actors – the populist parties themselves – who can often declaim with greater authenticity in the defence of national identity and greater security.

The third strategy is to ‘change the political agenda’. The greatest lesson from the link between populism in power and the migrant question is that populists are hardest to defeat on their own turf. The most powerful weapon of the populists is to divert the political agenda from the usual, mainstream economic and social topics and approaches, to topics such as the corruption of the elites, nationalism, immigration or even different conspiracy theories. In these topics, it is possible to give simplistic answers that mainstream parties have a hard time competing with. Immigration and the refugee crisis are the populists’ ‘own’ topics; if this is the political agenda, then populists are playing on their home turf.

The essence of the third strategy is for the left to acknowledge that it will be unable to create a social majority for its own politics regarding refugees: it is impossible to win elections with a leftist ideological answer to the refugee crisis. The more the political agenda is dominated by the question of refugees, the more populist parties will gain support, and the more countries they will rise to power in. In the end, despite the left’s best efforts, it is the refugees who will suffer the most from this process.

The key to reformulating the political agenda is for the left to sustain its pro-refugee stance, but to focus all its energies on avoiding this topic in European public life. Leftwing parties can stop populism from gaining even more ground if they divert the political agenda away from topics that are easy for populists to exploit, and if they will be the ones to dictate the criteria for a country’s successful government, once again. The left can regain its old strength if European politics will be about social Europe, about the reduction of social inequality, about higher pay for workers, about improving health and education, and not at all about the question of refugees.

This article was originally published by Progressive Britain