The Fourth Industrial Revolution is challenging the future of work. Technological change and automation risk making jobs redundant. But the naysayers are wrong. Automation doesn’t mean the end of work – we just need to get ready for the changes on the horizon.

Technological change is increasingly turning the value chain into an automated and digitalised process. The digitalisation and automation of manufacturing processes is characterised by the use of increasingly autonomous systems and robots, as well as fully automated smart factories (Industry 4.0), which are interconnected with upstream and downstream business divisions. Similarly, service providers have been using intelligent software and algorithms on the basis of large volumes of data and web interfaces to digitalise and automate business processes. To this effect, businesses make use of big data analysis software, cloud computing systems or online platforms, to give but a few examples.

In view of these technological developments – sometimes referred to as technologies of the fourth industrial revolution – an increasing number of concerns have been voiced in the public debate that this might lead to many jobs becoming redundant in the future. The idea of ‘technological unemployment’ is supported by a number of US studies which suggest that almost 50% of jobs are at risk of being replaced by new digital technologies (Frey and Osborne 2017). This raises a number of questions for both political decisionmakers and the general public: is it true that automation and digitalisation will result in major job losses? And if so, which jobs are at risk? In what ways are technological developments changing work processes and content? How will this affect qualification and skills requirements? Do we need to adapt in order to guarantee employee job security? This essay sheds some light on these questions.

Automation risks seem to be overestimated

Frey and Osborne (2017) investigated how susceptible are jobs to computerisation by asking experts how easily certain occupations could be automated in the next two decades. As a result they estimate that 47% of all US employees are in occupations that are at high risk of becoming automatable in the next 10 to 20 years. Applying the same methods to determine the automation potential of specific occupations in Germany and Europe yields similar results (Bonin, Gregory and Zierahn 2015; Bowles 2014). Hence, these findings subsequently spurred widespread automation angst and have sparked lively political debate public debate in recent years. However, there are good reasons to assume that these figures vastly overestimate the number of jobs that will actually become redundant due to technological advances in the next two decades.

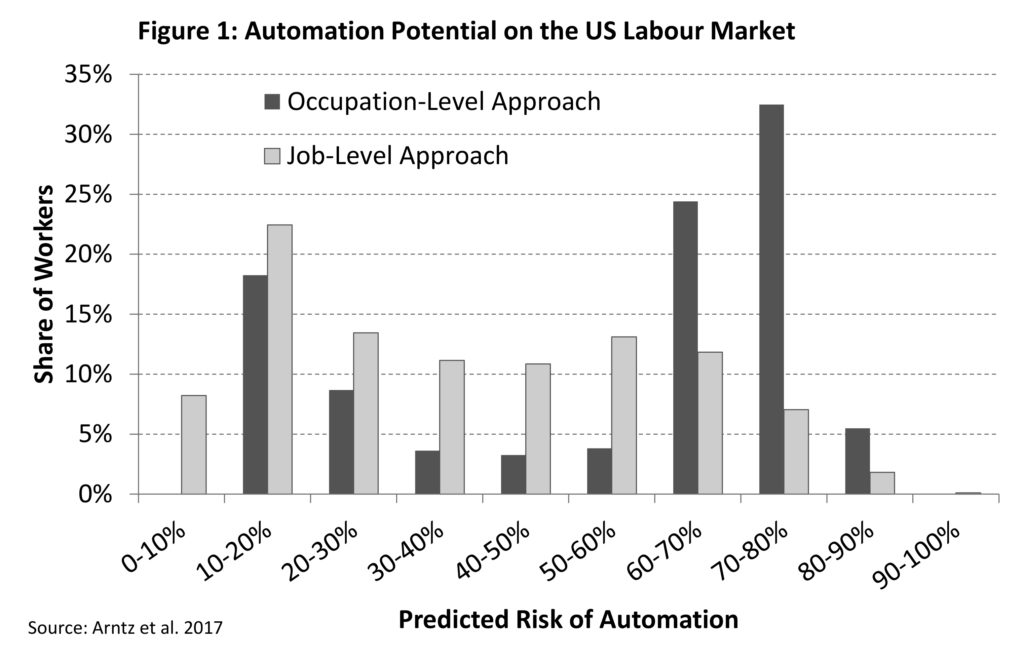

First of all, usually, not all the tasks outlined in a job description can be automated to the same degree. In fact, though machines may take over certain tasks of any given job description, there are others that they cannot. Therefore, whether an occupation can be automated or not depends on how significant the type of tasks are that can be carried out by machines. Hence, even within the same occupation, the automation potential can vary greatly from job to job. An analysis of automation potential based on the actual task structure of individual jobs thus produces very different results (see Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn 2017). According to this analysis, the percentage of jobs in the US with a high automation potential (>70%) falls from 38% when applying Frey and Osborne’s occupation-based approach to just 9% when looking at individual jobs (see Figure 1). One explanation for this significantly reduced automation potential is that many jobs involve tasks that are difficult to automate and that workers apparently specialise in different non-automatable niches within their profession. As a result, risk assessments that are based on occupational job descriptions for some representative workers do not sufficiently capture these non-automatable niches, and hence seriously overestimate the potential for automation. One potential reason for this result could be that workers increasingly shift their work towards tasks that complement these new technologies (Spitz-Oener 2006).

These findings also hold for many other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. In particular, the use of an individual job-oriented approach has shown that the automation potential of jobs in 21 OECD countries is far lower than previous studies would have us believe (Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn 2016), though the results vary from country to country. While 12% of jobs in Germany and Austria can be automated, the figure for Korea is only 6%. Even though the cause-and-effect relationship is yet to be sufficiently studied, the analysis suggests that countries with the lowest percentage of jobs that can be replaced tend to invest more in information and communications technology (ICT) and have a more communication-intensive workplace structure as well as a more highly educated workforce. Hence, there is some evidence that the automation potential has been exaggerated and that future potential for automation is actually lowest in the countries that have already undergone some adjustments through ICT investment and upskilling their workforce. Notably, these expert-based risk assessments also correspond more or less with subjective assessments of employees regarding technological change; according to a German survey, 13% of workers expect their job to be carried out by a machine within the next 10 years (Arnold et al. 2016).

Hurdles to digitalisation limit automation potential in the short- to mid-run

Although the automation potential may thus be much lower than is often claimed, around 1 in 10 jobs still seems to have the potential to become automated. Expecting an increase in unemployment of the same magnitude, however, would be much too simplistic a conclusion, since automation potential only reflects the technical potential for job displacement (see also Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn 2016; Bonin, Gregory and Zierahn 2015). For example, it is quite likely that it takes longer for these new technologies to be adopted by firms on a grand scale than is often asserted. Initial analyses based on the representative IAB-ZEW Working World 4.0 survey conducted in early 2016 have shown that although around half of German companies are using “technologies of the fourth industrial revolution”, on average only 5% of all firm assets could be described as “production facilities 4.0” and only 8% as “electronic office and communications equipment 4.0” (Arntz et al. 2016b).

Some of the main hurdles faced by firms when implementing technologies of the fourth industrial revolution are the increasing cost of data protection and cyber security measures, the need for specific training for employees on how to work with new technologies, high investment costs, and an increased dependence on external knowledge and services (Arntz et al. 2016a). Apart from these hurdles, a number of regulatory, legal or social road blocks do not prevent the introduction of these new technologies, but they could slow their diffusion. Some of the obstacles will be overcome at some point. Social preferences for certain tasks to be carried out by humans rather than machines (eg in areas such as care services) may limit the adoption of new technologies even in the long run. This could be done by establishing technical standards for implementing networked manufacturing and liability issues surrounding self-driving cars.

Digitalisation is changing jobs but not replacing them

The implementation of new technologies does not necessarily lead to job losses if employees are increasingly carrying out tasks that are made more efficient by using new technologies without being replaced by these technologies (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017; Autor 2015). This may also explain why only a third of the 13% of employees who believe their job could potentially be automated expressed concern over the security of their own job (Arnold et al. 2016). Since, from the perspective of companies, the use of new technologies goes hand in hand with increased work productivity as well as additional sales opportunities for new products and services (Arntz et al. 2016b), the effects of digitalisation on overall employment are not necessarily negative.

Technological change creates more jobs than it destroys

In order to make any concrete statement on the changes to overall employment over the course of digitalisation, we must consider both labour-saving and job-creating effects. From their initial empirical findings on the European level, Gregory, Salomons and Zierahn (2016) concluded that the net balance was previously on the whole positive. Figure 2 shows the corresponding aggregate effect of technological change in the period 1999–2010 on the labour demand of firms and dissects it into various causal factors. The lower limit is based on the assumption that only wage income leads to increased consumption in Europe, while the upper limit assumes that capital income also has a positive effect on the European economy through consumption. Overall, it appears that labour demand has increased as a result of recent technological change. The labour-creating effect of technological change thus seems to dominate the initial labour-saving effect. This is because the falling price of goods, together with increased consumption resulting from rising income levels, have led to an increase in labour demand in both the area of tradeable goods (this is an example of the positive product demand effect) and of non-tradeable services (this is an example of the positive product demand spillover effect). The latter effect is considerably stronger if capital income also contributes to consumption within Europe. This suggests that the effects of digitalisation on the labour market might also depend on how the profits of technological change are distributed and utilised.

References

Acemoglu, D. and D. Autor (2011), ‘Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings’, in O. Ashenfelter and D. Card (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 4, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Acemoglu, D. and P. Restrepo (2017), ‘The Race Between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares and Employment’, unpublished.

Arnold, D., S. Butschek, D. Müller and S. Steffes (2016), ‘Digitalisierung am Arbeitsplatz: Aktuelle Ergebnisse einer Betriebs- und Beschäftigtenbefragung’, Forschungsbericht im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Arbeit und Soziales und des Instituts für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, Berlin.

Arntz, M., T. Gregory and U. Zierahn (2016), The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: a Comparative Analysis, Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper 189, Paris: OECD.

Arntz, M., T. Gregory and U. Zierahn (2017), ‘Revisiting the Risk of Automation’, Economics Letters, 159: 157–60.

Arntz, M., T. Gregory, S. Jansen and U. Zierahn (2016a), ‘Tätigkeitswandel und Weiterbildungsbedarf in der Digitalen Transformation’, Studie des Zentrums für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung (ZEW) und des Instituts für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung (IAB) im Auftrag der Deutschen Akademie der Technikwissenschaften (acatech).

Arntz, M., T. Gregory, F. Lehmer, B. Matthes and U. Zierahn (2016b), ‘Arbeitswelt 4.0 – Stand der Digitalisierung in Deutschland: Dienstleister Haben die Nase Vorn’, IAB Kurzbericht, 22.

Autor, D. (2015), ‘Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3): 3–30.

Bonin, H., T. Gregory and U. Zierahn (2015), Übertragung der Studie von Frey/Osborne (2013) auf Deutschland, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, ftp://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/gutachten/Kurzexpertise_BMAS_ZEW2015.pdf.

Bowles, J. (2014), ‘The Computerisation of European Jobs’, blog, 24 July, Bruegel, http://bruegel.org/2014/07/the-computerisation-of-european-jobs/.

Frey, C. B. and M. Osborne (2017), ‘The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerization?’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114: 254–80.

Gregory, T., A. Salomons and U. Zierahn (2016), ‘Racing With or Against the Machine? Evidence from Europe’, ZEW Discussion Paper, 16(53).

Spitz‐Oener, A. (2006), ‘Technical Change, Job Tasks, and Rising Educational Demands: Looking outside the Wage Structure’, Journal of Labor Economics, 24(2): 235–70.

Wolter, M. I., A. Mönnig, M. Hummel, C. Schneemann, E. Weber, G. Zika, R. Helmrich, T. Maier and C Neuber-Pohl (2015), ‘Industrie 4.0 und die Folgen für Arbeitsmarkt und Wirtschaft. Szenario-Rechnungen im Rahmen der BIBB-IAB-Qualifikations- und Berufsfeldprojektionen’, IAB Forschungsbericht, 8.